Essay Thirteen Part One: Lenin's Disappearing Definition Of Matter

Unfortunately, Internet Explorer 11 will no longer play the video I have posted to this page. As far as I can tell it plays as intended in other Browsers. However, if you have Privacy Badger [PB] installed, it won't play in Google Chrome unless you disable PB for this site (anti-dialectics.co.uk).

.

[Having said that, I have just discovered they play in IE11 if you have upgraded to Windows 10! It looks like the problem is with Windows 7 and earlier versions of that operating system.]

If you are using Internet Explorer 10 (or later), you might find some of the links I have used won't work properly unless you switch to 'Compatibility View' (in the Tools Menu); for IE11 select 'Compatibility View Settings' and add this site (address above). Microsoft's browser, Edge, automatically renders these links compatible; Windows 10 and Windows 11 do likewise.

However, if you are using Windows 10 or 11, IE11 and Edge unfortunately appear to colour these links somewhat erratically. They are meant to be mid-blue, but those two browsers render them intermittently light blue, yellow, purple and red!

Firefox and Chrome seem to reproduce them correctly, as far as I can tell.

Several browsers also underline these links erratically. Many are underscored boldly in black, others more lightly in blue! They are all meant to be the latter.

Finally, if you are viewing this with Mozilla Firefox, you might not be able to read all the symbols I have used; Mozilla often replaces them with an "º'. There are no problems with Chrome, Edge, or Internet Explorer, as far as I can determine.

I have no idea if that is the case with other browsers.

[DM = Dialectical Materialism/Materialist, depending on the context; HM = Historical Materialism/Materialist, also depending on the context.]

As is the case with all my work, nothing here should be read as an attack either on HM -- a scientific theory I fully accept --, or, indeed, on revolutionary socialism. I remain as committed to the self-emancipation of the working class and the dictatorship of the proletariat as I was when I first became a revolutionary over thirty-five years ago. The difference between DM and HM, as I see it, is explained here.

Some readers might wonder why I have quoted extensively from a wide variety of DM-sources in the Essays published at this site. In fact a good 10-20% of the material in many of them is comprised of just such quotations. Apologies are therefore owed the reader in advance for the length and extremely repetitive nature of most of these quoted passages. The reason for their inclusion is that long experience has taught me that Dialectical Marxists simply refuse to accept that their own classicists -- e.g., Engels, Plekhanov, Lenin, Trotsky and Mao, alongside countless 'lesser' DM-theorists --, actually said the things I have attributed to them. That is especially the case after they are confronted with the absurd consequences that flow from their words; and that remains the case unless and until they are shown chapter and verse and in extensive detail. In debate, when I quote only one or two passages in support of what I allege, they are simply brushed off as a "outliers" or as "atypical". Indeed, in the absence of dozens of proof texts drawn from many such sources (across all areas of Dialectical Marxism) they tend to regard anything that a particular theorist had to say -- regardless of whether they are one of the aforementioned classicists -- as either "far too crude", "unrepresentative" or even(!) unreliable. Failing that, they often complain that any such quotes have been "taken out of context". Many in fact object since -- surprising and sad though this is to say --, they are largely ignorant of their own theory or they simply haven't read the DM-literature with due care, or at all! The only way to counter such attempts to deflect, reject and deny is to quote DM-material frequently and at length.

In addition, because of the highly sectarian and partisan nature of Dialectical Marxism, I also have to quote a wide range of sources from across the entire 'dialectical spectrum'. Trotskyists object if I quote Stalin or Mao; Maoists and Stalinists complain if I reference Trotsky -- or even if I cite "Brezhnev era revisionists". Non-Leninist Marxists bemoan the fact that I haven't confined my remarks solely to what Marx or Hegel had to say, advising me to ignore the confused, even "simplistic", ideas expressed by Engels, Plekhanov, Lenin, Stalin, Mao and Trotsky! This often means I have to quote the lot!

That itself has had the (indirect) benefit of revealing how much and to what extent they (the classicists and subsequent epigones across all areas of Dialectical Marxism) largely agree with each other (despite sectarian rhetoric to the contrary), at least with respect to DM!

Some critics have complained that my linking to Wikipedia completely undermines the credibility of these Essays. When I launched this project on the Internet in 2005, for the vast majority of topics there was very little material easily available on-line to which I could link other than Wikipedia. In the intervening years alternative sites have become available (for example, the excellent Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy), so I have been progressively replacing most of the old Wikipedia links with links to these other sources. Having said that, I haven't done so for some of the Wikipedia links -- for instance, any that are connected with geographical, historical, scientific, biographical (etc.) topics, where the relevant areas aren't considered controversial, at least by fellow Marxists. In every instance, I have endeavoured to avoid linking to Wikipedia in relation to key areas of my arguments against DM so that at no point does my criticism of this theory/method depend exclusively on such links.

In addition to the above (as readers will soon see if they consult the Bibliography) I have provided copious references to other published academic and non-academic books and articles (posted on-line or printed in hard copy) in the End Notes to this Essay, which further develop or substantiate anything I argue, claim, allege or propose.

Others have complained about the sheer number of links I have added to these Essays (because they say it makes them very difficult to read). Of course, DM-supporters can hardly lodge that complaint since they believe everything is interconnected, and that must surely apply even to Essays that attempt to debunk that very idea. However, to those who find these links do make these Essays difficult to read I say this: ignore them -- unless you want to access further supporting evidence and argument for a particular point, or a certain topic fires your interest.

Still others wonder why I have linked to familiar subjects and issues that are part of common knowledge (such as the names of recent Presidents of the USA, UK Prime Ministers, the names of rivers and mountains, the titles of popular films, or certain words that are in common usage). I have done so for the following reason: my Essays are read all over the world and by people from all 'walks of life', so I can't assume that topics which are part of common knowledge in 'the west' are equally well-known across the planet -- or, indeed, by those who haven't had the benefit of the sort of education that is generally available in the 'advanced economies', or any at all. Many of my readers also struggle with English, so any help I can give them I will continue to provide.

Finally on this specific topic, several of the aforementioned links connect to web-pages that regularly change their URLs, or which vanish from the Internet altogether. While I try to update them when it becomes apparent that they have changed or have disappeared I can't possibly keep on top of this all the time. I would greatly appreciate it, therefore, if readers informed me of any dead links they happen to notice. In general, links to Haloscan no longer seem to work, so readers needn't tell me about them! Links to RevForum, RevLeft, Socialist Unity and The North Star also appear to have died.

~~~~~~oOo~~~~~~

Phrases like "ruling-class theory", "ruling-class view of reality", "ruling-class ideology" (etc.) used at this site (in connection with Traditional Philosophy and DM), aren't meant to suggest that all or even most members of various ruling-classes actually invented these ways of thinking or of seeing the world (although some of them did -- for example, Heraclitus, Plato, Cicero, and Marcus Aurelius). They are intended to highlight theories (or "ruling ideas") that are conducive to, or which rationalise the interests of the various ruling-classes history has inflicted on humanity, whoever invents them. Up until recently this dogmatic approach to knowledge had almost invariably been promoted by thinkers who either relied on ruling-class patronage, or who, in one capacity or another, helped run the system for the elite.**

However, that will become the central topic of Parts Two and Three of Essay Twelve (when they are published); until then, the reader is directed here, here and here for more details.

[**Exactly how and why this applies to DM will, of course, be explained in the other Essays published at this site (especially here, here, and here). In addition to the three links in the previous paragraph, I have summarised the argument (but this time aimed at absolute beginners!) here.]

The aim of this Essay is to examine in greater detail the comments that Lenin (and to a lesser extent other comrades) have made about the nature of matter and our apprehension of it. In addition, several other issues arising from Lenin's much-maligned book (MEC) will also be tackled.

[MEC = Materialism and Empirio-Criticism; i.e., Lenin (1972).]

It is also worth mentioning that a good 50% of my case against DM has been relegated to the End Notes. This has been done to allow the main body of the Essay to flow a little more smoothly. In many cases, I have added numerous qualifications, clarifications, and considerably more detail to what I have to say in the main body. In addition, I have raised several objections (some obvious, many not -- and some that will have occurred to the reader) to my own arguments -- which I have then answered. [I explain why I have done this in Essay One.]

If readers skip this material, then my answers to any qualms or objections readers might have will be missed, as will my expanded comments and clarifications.

[Since I have been debating this theory with comrades for over 25 years, I have heard all the objections there are! Many of the more recent on-line debates are listed here.]

Finally, much of this Essay still exits only in note form; what you see here are those parts I have deemed fit to publish. At a later stage, when other Essays have been finished, I will re-post this Essay with these extra notes written up for publication.

~~~~~~oOo~~~~~~

As of February 2025, this Essay is just under 82,000 words long; a much shorter summary of some of its main ideas can be accessed here.

The material below does not represent my final view of any of the issues raised; it is merely 'work in progress'.

[Latest Update: 22/02/25.]

Anyone using these links must remember that they will be skipping past supporting argument and evidence set out in earlier sections.

If your Firewall/Browser has a pop-up blocker, you will need to press the "Ctrl" key at the same time or these and the other links here won't work!

I have adjusted the font size used at this site to ensure that even those with impaired vision can read what I have to say. However, if the text is still either too big or too small, please adjust your browser settings!

(1) Introduction

(a) Lenin And 'Vanishing' Matter

(a) Is Matter Dependent On Mind?

(b) Hasty Repairs

(4) Some Things Aren't Material

(a) Externalism And Its Discontents

(b) Colour

(c) Other Contentious Examples

(a) At Last -- Lenin Constructs An Argument!

(b) Bluster Central

(c) Image Conscious

(d) Tumblers

(e) Hold The Press! Did Lenin Really Believe In Santa Claus? Surely Not!

(f) Images Fail To Make The Grade

(h) Lenin's Answer

(6) 'Objectivity'

(a) WTF Is It?

(b) 'Subjective' No Less Defective

(d) Lenin, Objectivity And Existence

(7) What Exactly Is Dialectical Materialism?

(b) Is Matter Just An Abstraction?

(c) Cherry Picking

(d) Prevarication -- One Thing Dialecticians Do Well

(e) Lenin 'Advances' By Going Backwards

(8) Notes

(9) References

Summary Of My Main Objections To Dialectical Materialism

Abbreviations Used At This Site

Essay Thirteen will largely be concerned with what might loosely be called 'scientific issues'. Part One will focus on Lenin's attempt to 'define' matter (or rather, his successful attempt to avoid telling us what it is!), and the means by which he thinks we come to know it, or know about it. In the course of which I hope to show that Lenin's theory of knowledge -- or, more specifically, his focus on "images" as the basic source of our knowledge -- undermines not just the nature of matter, but scientific knowledge itself.

Part Two (to be published sometime in 2023) will concentrate on the attempts made by DM-theorists to understand science and scientific change in general; Part Three will examine in detail their efforts to analyse language and cognition -- concentrating largely on Voloshinov and Vygotsky along with several more contemporary DM-theorists. In the process of which I will also examine what dialecticians have to say about the nature and evolution of language. In order to do that I will endeavour to show how and why dialecticians have carelessly allowed various ruling-class forms-of-thought to compromise theories of theirs devoted to these topics, as they have in relation to other areas (which we saw in earlier Essays). More specifically, I will show how their commitment to the Platonic-Christian-Cartesian Paradigm (introduced largely via Hegel's Mystical Hermeticism) -- a serious error that was further compounded by their acceptance of traditional forms of Representationalism -- has led them astray.

[DM = Dialectical Materialism/Materialist, depending on context.]

In MEC, Lenin attempted to confront, and then refute, contemporaneous interpretations of physics that appeared to him to question the reality of matter. Time and again he asserted things like the following:

"[T]he sole 'property' of matter with whose recognition philosophical materialism is bound up is the property of being an objective reality, of existing outside our mind." [Lenin (1972), p.311.]

"Thus…the concept of matter…epistemologically implies nothing but objective reality existing independently of the human mind and reflected by it." [Ibid., p.312.]

"[I]t is the sole categorical, this sole unconditional recognition of nature's existence outside the mind and perception of man that distinguishes dialectical materialism from relativist agnosticism and idealism." [Ibid., p.314.]

"The fundamental characteristic of materialism is that it starts from the objectivity of science, from the recognition of objective reality reflected by science." [Ibid., pp.354-55.]1

Lenin insisted on maintaining this view in the face of the revolutionary new concepts that were being introduced into the Physics of his day, which, under certain interpretations, seemed to indicate that matter did not exist -- at least, not as it had previously been understood. Lenin was fully aware of these changes; however, he argued that those who think this refutes materialism ignore:

"…[the] basis of philosophical materialism and the distinction between metaphysical materialism and dialectical materialism. The recognition of immutable elements…and so forth, is not materialism, but metaphysical, i.e., anti-dialectical, materialism…. Dialectical materialism insists on the approximate, relative character of every scientific theory of the structure of matter and its properties; it insists on the absence of absolute boundaries in nature, on the transformation of moving matter from one state into another." [Ibid., p.312.]

Again, concerning those who claimed that these new developments made the idea of matter redundant, he had this to say:

"[T]he expression 'matter disappears', 'matter is reduced to electricity', etc., is only an epistemologically helpless expression of the truth that science is able to discover new forms of matter, new forms of material motion, to reduce the old forms to the new forms, and so on." [Ibid., p.378.]

In addition, Lenin would have nothing to do with the idea that matter was simply energy:

"If energy is motion, you have only shifted the difficulty from the subject to the predicate, you have only changed the question, does matter move? into the question is energy material? Does the transformation of energy take place outside the mind, independently of man…or are these only ideas?… Energeticist physics is a source of new idealist attempts to conceive motion without matter." [Ibid., pp.324, 328.]

In these passages, Lenin's views were consistent with those he expressed elsewhere (even if his ideas developed considerably over the next ten years). It is also worth noting that Lenin clearly saw no problem with running together epistemological and ontological issues, just as it is equally obvious that he failed to appreciate the extent to which this undermined his entire world-view -- fatally compromising several core DM-theses along the way.2

In fact, despite his repeated protestations to the contrary, what Lenin wrote in MEC amounted to the abandonment of belief in anything that is recognizably material.

Small wonder then that he looked to that notorious Idealist, Hegel, for philosophical advice.

As is easily confirmed, Lenin didn't actually tell his readers what he thought matter was; indeed, he explicitly refused to do so.4 In common with other DM-theorists, he confined his comments concerning the nature of matter to a few rather vague statements, statements which, as things turn out, fatally compromise its presumed ontological status, and hence the status of DM as a materialist theory.

Turning to what Lenin actually said, he appeared to believe that it was a necessary and sufficient condition for something to be material that it should exist "outside the mind" as an "objective reality". Apart from a few passing comments about matter and physical reality, that is all he had to say about this supposedly core DM-concept! While he pointedly brushed aside familiar, traditional definitions of matter -- i.e., its impenetrability, composition, inertia, location in space and time, causal interaction, extension, etc. (cf., p.311) --, he continually referred to matter as that which exists as an "objective" reality "external" to, and "independent" of "consciousness".

He clearly regarded this criterion to be both a necessary and sufficient condition for something to count as material. This can be seen by the way he posed the following question:

"If energy is motion, you have only shifted the difficulty from the subject to the predicate, you have only changed the question, does matter move? into the question is energy material? Does the transformation take place outside the mind…?" [Ibid., p.324.]

Presumably, the background reasoning was something like the following:

L1: Any transformation that takes place (objectively) outside the mind is material.

L2: This particular transformation takes place (objectively) outside the mind.

L3: Therefore, it is material.

Hence, an affirmative answer to the following questions would provide sufficient grounds for the conclusion to follow (i.e., L3):

"...[D]oes matter move? [becomes]...the question is energy material? Does the transformation take place outside the mind…?" [Ibid., p.324.]

If Lenin's criterion had merely been a necessary condition, the above questions would have been pointless, since the conclusion (L3) wouldn't have followed (that is because, outside of mathematics and other formal disciplines, a necessary condition on its own plainly isn't sufficient).

Moreover, had Lenin's strictures merely been sufficient (but not necessary), they wouldn't have ruled out the possibility that material and mental entities or processes are coterminous (a là Spinoza, perhaps?), or even identical. Indeed, if it wasn't essential (i.e., necessary) that material processes take place extra-mentally, his criterion would have been totally useless.

Hence, Lenin's criterion was both necessary and sufficient. I propose to call this requirement (when augmented with additional DM-theses outlined below), "Externalism".

Externalism appears to be committed to one or more of the following theses:

T1: There exists a world that is both external to, and independent of, the human mind. Material objects and processes pre-date any and all minds. Mind depends on matter, not vice versa.

T2: This world exists objectively -- which means that it pre-existed human evolution --, and is independent of all cognitive capacities.

T3: The world is composed of objects, processes, relations and events in continual change.

T4: None of these are independent of each other; all are interconnected.

T5: Scientific knowledge of the world (coupled with practice) is our most reliable guide to its nature and laws.

T6: Our knowledge of the world is continually changing as our understanding grows and develops.

T7: There are no a priori limits to what we can know about the world, and our knowledge is subject to continual revision.

T8: Knowledge is historically-conditioned, but it isn't reducible to such conditioning (otherwise T1 and T2 would be compromised).5

Earlier on (in Essays One to Eight Part Three), the tensions that exist between this view of the world and those aspects of DM-epistemology that supposedly underpin it were examined in detail. It was argued there that DM-theses -- like those above --, when coupled with DM-epistemology, collapse into Idealism.

Notwithstanding this, it might seem possible to challenge that conclusion if, say, theses T1 and T2 above turn out to be correct.

Despite this, there are serious problems with all of the above theses, not least with T1, T2 and T4:

T1: There exists a world that is both external to, and independent of, the human mind. Material objects and processes pre-date any and all minds. Mind depends on matter, not vice versa.

T2: This world exists objectively -- which means that it pre-existed human evolution --, and is independent of all cognitive capacities.

T4: None of these are independent of each other; all are interconnected.

If certain parts of nature are indeed independent of each other (as T1 and T2 assert) then not all of reality is interconnected, contrary to what T4 says. T1 and T2 claim that while mind is dependent on matter, matter isn't dependent on mind. In that case, clearly, matter and mind cannot be inter-dependent. Although they might be connected, they cannot be inter-connected (in this sense).

Even if we grant for the present that the human mind is dependent on all the matter in the universe (i.e., on the "Totality", full-blown -- if, that is, the universe is the "Totality"; on that, see here), it is a pretty safe bet that no 'Materialist Dialectician' would want to argue that the converse is the case: that is, that any or all matter in the universe is dependent on mind. Naturally, that idea wouldn't have bothered Hegel too much, but it is reasonably clear that DM-theorists may only accept this converse idea as true if they are prepared to abandon materialism.5a

Nevertheless, it is surely an empirical matter whether or not any of the above conditions actually obtain (including the alleged fact that certain parts of reality are dependent on each other). Or, rather, it is to those who refuse to impose DM on nature -- as dialecticians constantly declare is the case with them.

Despite this, we have seen that DM-theorists appear to regard T4 as an a priori truth of some sort, since they tell us that everything in reality is interconnected (follow that link for proof), and they assert this in advance of there being an adequate body of supporting evidence to that effect. In that case, if they are consistent, they should draw the conclusion that their belief in universal inter-connectedness also commits them to the equally a priori view that every atom in the universe does in fact depend on the human mind.

Either that, or they should jettison the idea that everything in reality is inter-connected.

Well, perhaps this is being a little too hasty. Maybe the above 'difficulty' has arisen because of the emphasis DM-theorists place on the unity of knowledge and the identity (in difference) of knowledge and 'Being', and/or 'the thing-in-itself'. As Lenin tells us:

"There is definitely no difference in principle between the phenomenon and the thing-in-itself, and there can be no such difference. The only difference is between what is known and what is not yet known." [Lenin (1972), p.110.]

Admittedly, these ideas are often further qualified with the extra claim that this identity doesn't deny the primacy of matter over mind, nor does it imply that knowledge isn't relative or approximate, nor does it imply that the 'knower' and the 'known' are the same. Far from it, they tell us that they are dialectically inter-related.6

Could this help solve the problem posed above and show how mind can be dependent on matter, but not the other way round, while holding on to the thesis that everything is inter-connected?

Unfortunately, even if all the above considerations were either relevant or valid, the status of T1 and T2 would still fatally compromise T4. That is because, if T1 and T2 were true, it would mean that while our knowledge of nature (at least) was in fact dependent on the physical universe (mediated perhaps by social development and practice, etc.), the opposite couldn't be the case. That is, it wouldn't be true to say that the world as a whole is dependent on our knowledge of it howsoever much 'dialectics' we threw at it. Plainly, this would in turn imply that there is something in existence (i.e., the 'content' of our minds) which, while it is connected with, it isn't inter-connected with, the rest of the universe. In that case, the alleged link must be one-way, not two-way, undermining T4.

[Henceforth, I will often drop the hyphen between "inter" and "connected. It was only introduced to help make the above points a little clearer.]

If matter isn't connected with mind (in the above sense), then not everything can be interconnected.

It is far from clear how waving the word "dialectical" about can solve this conundrum.

T1: There exists a world that is both external to, and independent of, the human mind. Material objects and processes pre-date any and all minds. Mind depends on matter, not vice versa.

T2: This world exists objectively -- which means that it pre-existed human evolution --, and is independent of all cognitive capacities.

T4: None of these are independent of each other; all are interconnected.

On this view then, even if human activity has, or had, a limited and local affect on nature (confined at present to the Earth and this part of the Solar System), it would still mean that most of the universe is unaffected by what is known about it, or with what humanity is capable of thinking, or is capable of interacting with and then manipulating in practice. Hence, given Externalism, while the configuration of matter inside each of our heads might very well be causally linked to nature in one direction -- which configuration is supposedly responsible for the 'emergence' of 'consciousness' --, it wouldn't be 'back-related', as it were, to most of the rest of the universe.6a

Once again, while there would certainly be a connection here, there wouldn't be an interconnection.

The introduction of practice into the story at this point wouldn't help, either, nor would it reduce the serious nature of the difficulties Externalism faces: plainly, most of the universe is too far away for human beings to affect in any way at all. So, while distant parts of the universe might influence our knowledge of them, the human mind has no return effect on the vast bulk of the universe on the return journey, as it were. And, even if a 'sort of link' could be shown to exist (in that it requires human 'consciousness' to arrive at any such conclusions about distant parts of the universe), remote regions of space would clearly not be dependent on our mental activity. In short, most of reality, past, present and future is unaffected by, or isn't dependent on, our thoughts about it.

Plainly, those considerations are sufficient to remove the "inter" from "inter-related", fragmenting the Totality by making T4 false.7

Some might be tempted to think this is no big deal, and that the DM-Totality is unaffected by such quibbles. However, as we will soon see, that fall-back position only succeeds in putting off the evil day.

[Of course, the DM-'Totality' faces far more serious problems than these relatively minor points; on that, see Essay Eleven Parts One and Two.]

One way to avoid the above untoward conclusions might be to re-write T4 in the following manner:

T4a: Some elements of reality are independent of each other; others are interconnected.8

However, given the longevity and size of the universe, this would mean that T4a needs to be replaced with this, far more honest, alternative:

T4b: Some elements of reality are independent of each other and some aren't interconnected with the vast bulk of the rest of the universe.

Indeed, since the present is entirely ephemeral (while the past is either finite and extensive, or infinite), most events are, or will have taken place, in the past, not in the (now) present. But, unless we subscribe to the view that past events are somehow influenced by present events (i.e., unless we are prepared to admit that past events aren't just connected, they are interconnected with events in the present) --, T4b must be correct. That is, the vast majority of events in the history of the universe can't even be connected, let alone interconnected -- since they no longer exist. So, T4b completely undermines T4, turning an important DM-thesis into a rather bland statement -- and one over which few would want to get their metaphysical knickers in a twist.9

On the other hand, if T4 is still held to be true (and thus if T4b is rejected), what is in fact a potentially fatal defect re-emerges right at the heart of DM-epistemology. That is because it would imply that all of reality (past, present (and future?)) depends on our knowledge of it --, since T4 declares that everything is interconnected within the "Totality" -- and our thoughts surely exist somewhere in the universe.

So, it seems that the only way this Idealist conclusion can be avoided is if T4 is replaced by T4b. Unfortunately, as already noted, such a theoretical retreat would turn this DM-thesis (T4) into an uninteresting platitude (T4b).

Looking at things from the 'reverse direction', as it were, T1 and T2 themselves emphasise the fact that the link between the world and our knowledge of it -- or the connection between the human mind and reality itself -- is (largely) unidirectional. That is, they underline the fact that while our knowledge of the world is dependent on the material universe, the material universe isn't dependent on our knowledge of it. But, that is precisely what sinks T4. Hence, it looks like the only way to rescue these core DM theses (i.e., T1 and T2) is to abandon T4 altogether and replace it with the rather innocuous T4b.10

T1: There exists a world that is both external to, and independent of, the human mind. Material objects and processes pre-date any and all minds. Mind depends on matter, not vice versa.

T2: This world exists objectively -- which means that it pre-existed human evolution --, and is independent of all cognitive capacities.

T4: None of these are independent of each other; all are interconnected.

T4b: Some elements of reality are independent of each other and some are not interconnected with the vast bulk of the rest of the universe.

On the other hand, if T4 is left in place, that would imply matter is dependent on mind, as we have seen.

Clearly, while it might seem appealing to some to try to avoid this Idealist impasse by abandoning T4 (along the lines suggested above), the thesis that the "Totality" conditions everything by means of universal inter-relationships would collapse as a result. Along with this would go the doctrine that the entire nature of the part is determined by its relation to the whole, and thus that "truth is the whole". Hence, if some parts of the Totality aren't interconnected, then their individual natures can't be determined either by the whole or by each and every other part. As now seems plain, when this DM-Whole is allowed to develops just one small hole it soon begins to make a colander look rather leak-proof in comparison.10a

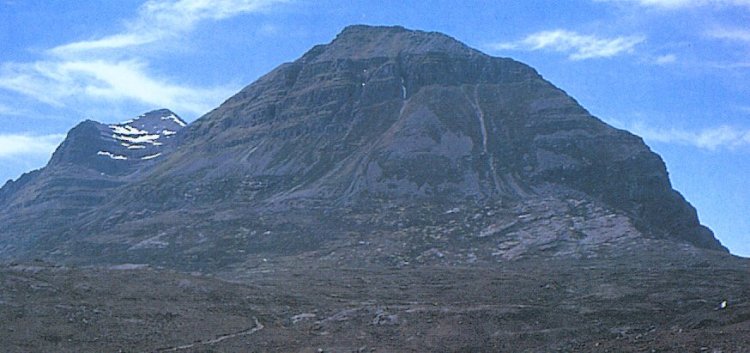

Figure One: Compared With DM, Relatively Leak-Proof!

Alternatively, we could tough it out and acknowledge the implicit Idealism in DM and admit that the world (including the past) is in fact conditioned by our knowledge of it, and that matter does depend on mind --, holding on to T4, but abandoning T1 and T2.

This would at least have the advantage of bringing closet DM-Idealists out, loud and proud, into the open.11

Externalism And Its Discontents

Ignoring the above problems for the present, and returning to Lenin's thoughts, he certainly regarded 'externality' as a criterion that distinguished rival Idealist theories from DM itself. That is obvious from the way he repeatedly castigated any opponent who denied, half-denied, or only half-heartedly accepted this condition.12

However, this raises another awkward question: if 'externality' is Lenin's sole criterion for materiality -- and is a necessary and sufficient condition for it, too --, what are we to say of the many non-material things there are that also seem to possess 'externality'? What about colours, smells, tastes, sounds, shapes, shadows, holes, surfaces, 'empty' space, relations, the Centre of Mass of the Galaxy (henceforth, CMG), averages (such as the average lager drinker), the past, the present and the future?

Now, some readers might consider most (if not all) of the above examples highly contentious. For example, it could be argued that colours are certainly material. However, such a response would be a mistake. Colour perception may have causal and/or material concomitants, but colours can't be material. If they were, it would make sense to ask of what they are composed.12a Of course, colour isn't made out of anything not already coloured and it has no constituent parts (which aren't already coloured, too). So such a question would have no answer that wasn't viciously circular (i.e., it would be rather like saying matter is made of matter).13

Again, it could be objected that colour is actually made out of photons of different energies, or of light of different wavelengths. However, that response simply confuses the causal agent responsible for our colour perception with colour itself.

Once more, it might be objected that colour is caused by the interplay between light rays and the microstructure of atoms, or that colour is a dispositional property of material objects -- or perhaps even a dispositional property of perceivers themselves. Whether these claims are true (or not) won't be entered into here; but, once again, these responses confuse the causal agents and/or concomitants responsible for colour perception with colour itself.14 As Professor Laurence Goldstein notes:

"Take blueness, for example. What enters our eyes -- the blue light -- is simply (objectively) electromagnetic radiation. Yet the electromagnetic radiation is not blue. Colour has at least three dimensions -- hue, brightness, and saturation -- and four of the hues -- red, green, yellow, and blue -- are primary, that is, visibly non-composite. There can be reddish blues, but no yellowish blues or reddish greens. Yet such characteristics of colour are not characteristic of electromagnetic radiation. For example, no unique wavelength can be identified with a unique hue, since identical colour experiences may be produced by different combinations of wavelength. So light of any particular wavelength cannot be identified with a colour, that is, light is not coloured.

"Blueness, then, is not a property of electromagnetic radiation. Perhaps it is a property possessed by blue objects, that is, a property that they possess whether or not anyone is looking at them. But are objects intrinsically coloured? There is a strong temptation to suppose that all the objects that we perceive as blue have something, for example a certain molecular surface structure, that makes them so. Yet, when we actually conduct a detailed analysis of the different kinds of blue things that we see, it soon becomes clear that this supposition is incorrect. The blueness of the sky is due to the scattering of white light by particles of a certain size, and the same cause is responsible for the blueness of the eyes of some Caucasians and of the facial skin of many monkeys. But the blue of a rainbow has quite a different cause from that of the blueness of certain stars. And what makes sapphire blue is quite different from what makes some birds blue, and both are different from what causes the blue of certain beetles." [Goldstein (1990), pp.185-86. Spelling altered to conform with UK English. Italic emphases in the original. Links added.]

Although, Professor Goldstein finally concludes that colour isn't an "objective property of things" (p.186), that observation isn't so much false as non-sensical. [On the status of such hyper-bold claims about 'things-in-themselves', see Essay Twelve Part One. See also Stroud (2000).]

Be this as it may, the point is that Professor Goldstein is right when he points out that electromagnetic radiation itself isn't coloured.

Some, like the above Professor, might claim that colours are 'mental' phenomena and exist only in conscious minds, not in the external world. But, that, too, is an age-old mistake. Colours don't exist merely in the mind since (plainly!) they exist in the outside world; any theory that located colours exclusively in the minds of perceivers would clearly have misidentified them. So, when, for instance, a scientist describes Copper Sulphate crystals as blue, she is referring neither to the contents, nor to the state, of her mind or central nervous system. Anyone who thought otherwise would simply have drawn attention to their own misuse of language.15

Of course, Lenin would have been the first to point out that scientific materialism must incorporate into its view of the world all the properties of matter that scientists ('objectively') determine for it, including colour. But, the policy of waiting for scientists to tell us what reality does or doesn't contain isn't without its own problems (as we discovered in Essay Eleven Part One).

Hence, if scientists tell us that matter is little more than a convenient shorthand for the effect of scalar and/or vector fields (or Superstrings -- or anything else, for that matter -- no pun intended) on their measuring instruments, or on perceivers, it might well be wondered what there is left of the material world that could possibly act as the bearer of any properties at all. Indeed, given such an austere view of the world -- which pictures it as nothing more than a complex array of vectors, tensors, scalars, geodesics, differential equations, and the like --, the relationship between 'nature' and the 'mind' would amount to nothing more than a set of complex 'interactions' between one set of scalar/vector/tensor fields (i.e., "the world") and another set of scalar/vector/tensor fields (the "brain/mind", only now of dubious composition and constitution). Not only would matter more than appear to disappear (on this account), so would perceptions, thoughts and properties, too! In that case, both matter and 'mind' would seem to vanish; the entire universe would thus become an array of sets of…, well, what?16

To be sure, the serious problems DM-theorists face arose much earlier than this. By contracting-out to scientists the right to tell us what matter is, or what the world contains, Lenin and other dialecticians should feign no surprise when everything disintegrates in front of them, and the Idealism implicit in every aspect of class society (including that which influences and motivates certain areas of modern science) forces itself upon them.17

Nevertheless, we all already know what colour is (or, at least, competent speakers of the language already know) -- we learnt what it is when we were taught how to speak about it and how to interact with coloured objects. In fact, we must already understand what colour terms mean if we are to be informed by scientists what its physical concomitants and properties are supposed to be. We certainly couldn't be educated (or re-educated) by them concerning the physical nature of colour if no one understood what the word "colour" already meant.

That non-negotiable logico-linguistic constraint applies with equal force to scientists themselves; they too must grasp what ordinary colour terms mean (and they must do so in the same way that the rest of us do, or they won't be speaking about colour, but about 'colour') if they are to study successfully the physical properties of the correct natural phenomenon. So, scientists (and/or sceptics) can only undermine the ordinary use of the word "colour" (if that is what they do) at the cost of making all they say about 'it' entirely vacuous. If colour isn't what we suppose it to be when we use the ordinary language of colour, then we must surely lose the solid ground upon which scientists sought to build a properly scientific explanation of 'it'.18

This means that the claim that colour is a (dispositional) property of material objects can't be the whole truth about it, in that it isn't all that colour is. And this "all" can't be accommodated to any theory without a prior recourse to the ordinary language of colour. And, this has nothing to do with Lenin's "externalism", either, since, plainly, our perception of colour isn't independent of the existence of sensate life -- in this case, our own.19

Of course, it could be objected that the nature of colour is a scientific not a linguistic issue --, but that rejoinder would be equally misguided. As we saw earlier (in relation to the word "change"), it isn't up to scientists, philosophers or dialecticians to tell us what our colour words mean (and that constraint applies to the rest of our everyday vocabulary, too). Any attempt to do so would plainly undermine the language used in any endeavour to do just that.20

Again, it could be objected that this isn't something that can be settled by (or, indeed, brushed aside with) an appeal to the ordinary meaning of words. This is a scientific and/or a philosophical issue.

However, scientists, philosophers and/or dialecticians will have to use language in order to tell us what they take colour to be (i.e., if they are to address the right subject of their enquiries), and, plainly, in order to make a correct start they themselves will have to begin with terms drawn from the vernacular -- otherwise they would be aiming their comments at some other target, not colour.

Now, it is precisely here that any attempt to revise (or even tinker with) the vocabulary of colour that we already have will back-fire. Since the details underlying that observation have been worked-out in detail elsewhere, and because further discussion will take us too far from the main theme of this Essay, I will leave the reader to re-familiarise herself with that discussion (in the course of which, she will need to replace the word "change" with the colour terms of her choice).

Naturally, this is a contentious topic, and not one around which I want this Essay to revolve. So, let us consider some of the other items mentioned above; Lenin's criteria would categorise holes, surfaces and shadows, for instance, as 'material' (in that they are "external to the mind") -- but, plainly, they are in no way material.20a Not, that is, unless the word "material" is re-defined to make them so -- in which case, this part of Lenin's theory would become 'true' simply because of yet another example of terminological tinkering.

It would also mean that this area of DM, at least, will have been imposed nature, not 'read from it'.21

And what is so material about the relations between bodies and/or processes? But such relations are 'external to the mind'. In that case, given Lenin's criteria, the distance between you and the planet Jupiter, say, is just as material as you are! And so is the fact that you are smaller than Jupiter (if you are).21a

Indeed, several of the other items from the above list of allegedly non-material entities appear to be equally if not more problematic than the nature of colour, relations, holes and shadows. What, for example, are we to make of the CMG? It is clearly not material (in fact it doesn't physically exist in any meaningful sense -- it occupies a zero volume interval in space, for example), and yet it exercises a decisive causal influence on the movement of every particle in the entire Galaxy. But, the CMG is manifestly 'external to the mind', so it must be 'objective', according to Lenin. But, is there anything actually in reality that 'corresponds' with it?

Should a hard-nosed supporter of Lenin be tempted to argue that the CMG is material just because it is external to the mind, then we would be owed an explanation as to how something that has no physical correlate could possibly be material. This requirement would, of course, be accompanied by yet another annoying reminder that a brave 'dialectical' conclusion such as this could only ever have been imposed on nature.22

Again, it could be objected that the CMG is surely a consequence of all the matter in the Galaxy. But, the CMG is actually part of a mathematical model that we use to explain motion. Nothing actually exists in the outside world that answers to 'it', and yet 'it' is certainly not located inside our skulls (any more than the Prime Meridian is).

Moreover, the CMG can't be a property of matter since it doesn't exist in the same way that material bodies and their properties do (it doesn't share any of the features or the properties of tables and chairs, atoms and galaxies, for example). In fact, the claim that the CMG is a property of all the matter in the Galaxy is about as accurate as the idea that the average lager drinker is a property of all (or any) lager drinkers. Of course, in this case, if 'he/she' -- i.e., the average lager drinker -- were a property, 'he'/'she' couldn't then be a 'he' or a 'she', and hence wouldn't be an average person to begin with.23

It is becoming obvious that Lenin's "externality" thesis permits (or could permit) the existence of several non-material things -- in addition to the above, such things as lines of force, mirages, optical illusions, the perspectival properties of bodies, vectors, tensors, scalars, co-ordinate systems, and so on -- all the while ruling out-of-court other seemingly material things (like, 'the mind' itself).24 In addition, the past, present and future seem to pose problems for Lenin in that they all appear to possess "externality", but neither is obviously material -- nor are they the consequence of the properties of material objects (or, at least not in any obvious way).25

Worse still, empty space doesn't appear to be material, either.26 In fact, Lenin himself believed in the existence of the Ether:

"That is why Engels gave the example of the discovery of alizarin in coal tar and criticised mechanical materialism. In order to present the question in the only correct way, that is, from the dialectical materialist standpoint, we must ask: Do electrons, ether and so on exist as objective realities outside the human mind or not? The scientists will also have to answer this question unhesitatingly; and they do invariably answer it in the affirmative, just as they unhesitatingly recognise that nature existed prior to man and prior to organic matter. Thus, the question is decided in favour of materialism, for the concept matter, as we already stated, epistemologically implies nothing but objective reality existing independently of the human mind and reflected by it." [Lenin (1972), p.312. Bold emphases added.]27

And, Lenin was still referring to the Ether several years later, in PN! [Cf., Lenin (1961), p.250.]

Unfortunately, the Ether doesn't exist, and never did -- even though Lenin here describes it as an "objective" feature of reality, simply because it passed his "externality" test (and it seemed to conform with contemporaneous scientific fashion). If the existence of the Ether had ever in fact been "objective", that would suggest that something could be "objective" even though it didn't actually exist, and never did. In this particular case, that would in turn mean -- if Lenin's criterion for materiality were correct -- that although there is nothing in reality answering to it, the Ether would nonetheless be material. "Objectivity" would, of course, then become synonymous with "completely fictional in some cases". Naturally, that would fatally undermine Lenin's already shaky attempt to refute the ideas of the other Fictionalists and Idealists he was criticising in MEC.

As we saw earlier, Lenin seriously over-used the word "objective"; if the latter term now allows for the 'objectivity' of fictional entities, it would make Lenin's arguments about as convincing as Tony Blair's 'case' for the invasion of Iraq.28

At any rate, and despite what he thought, Lenin's 'imaginability'/'image-ability' criterion is neither necessary nor sufficient for something to count as 'objective'. That is because, as we have seen, there are countless things that exist outside the mind that aren't 'objective' in any clear sense of the term (e.g., mirages, the perspectival properties of bodies, surfaces, rainbows, corners, images in actual mirrors -- as well as statistically constructed entities, like the average worker), and there are 'objective' things that aren't external to the 'mind' (for example, the human 'mind' itself -- the word "mind" has been put in 'scare' quotes here for reasons that will be explained in Essay Thirteen Part Three) -- just as there are 'objective' material entities that are dependent on the human mind, and which are constituted in and by social activity (such as money, theatre tickets and revolutionary newspapers).

And, as if to complicate matters further, there are non-existent things (such as the Ether), that Lenin imagined were "objective"!

Indeed, what are we to make of the Ether? Was Lenin (or, has anyone ever been) able to form an image of this allegedly universal substance? If he (they) could, then according to the above passage it must exist. On the other hand, if he (they) couldn't form an image of it, why did Lenin think that it existed and was 'objective'?

More to the point, does the ability to form an image really matter? Who can form an image of four dimensional Spacetime? Or of a black hole? Or of a Superstring? Or of the CMG?

In fact, if imaginability/image-ability implied existence, science would surely be pointless; in such an eventuality we could rely on Hans Christian Andersen and Enid Blyton to inform us of the contents of reality, and abandon scientific research.

As is well-known, scientists were forced to conclude (in the end) that the Ether didn't exist, even though had it done so it would have satisfied Lenin's criterion of 'externality' (and it would have been 'objective' in that it would have existed independently of the mind).

[Oddly enough, some scientists (including Einstein and perhaps even Paul Dirac) still believe there is an Ether. And now, in 2011/12, there is even a Higgs-ether!29]

Nevertheless, whatever else might be true of Lenin's thoughts about material existence, it looks like scientists themselves require there be more to something than the mere possibility of its external existence (and/or its imaginability/image-ability) for it to be 'objective'.

Unfortunately, Lenin himself failed to inform his readers exactly why his 'criterion' should be adopted as a definition of matter (that is, if it was indeed a definition; on this, see Note 4) -- he just left it as a bald assertion that anything that existed 'objectively' outside the mind must be material, even when this clearly isn't a condition that only material objects satisfy or fulfil. For Lenin, it seems that just because something isn't inside the mind it must be material, otherwise it can't be. On that basis, as noted above, that would mean that the mind itself is neither 'objective' nor material! Lenin's criterion, therefore, appears to commit him to the existence of a non-material mind, since it plainly can't exist outside itself.

Paradoxically, therefore, it looks like Lenin's materialism is committed to the existence of non-material/immaterial minds!

If Lenin's 'criterion' is now watered-down, so that it allows the mind to enjoy some sort of 'objective' existence (perhaps as part of the activity of the brain, or maybe even as an "emergent" property of matter), then clearly 'externality' will have to be abandoned -- otherwise, there would be no point to Lenin's question (quoted earlier):

"If energy is motion, you have only shifted the difficulty from the subject to the predicate, you have only changed the question, does matter move? into the question is energy material? Does the transformation of energy take place outside the mind, independently of man…or are these only ideas?...." [Ibid., p.324. Bold emphasis added.]

As we have seen, this passage indicates that material objectivity is definitionally connected to externality in Lenin's own mind (i.e., as a necessary and sufficient condition).

However, and even worse, this quotation seems to imply that the mind uses no energy, that it has no 'objective' existence, or that it doesn't move. Plainly, any particular mind is 'external' to all other minds, which must mean that while every other mind is 'objective' in relation to any given mind (being external to each), it isn't 'objective' with respect to itself, since it isn't external to itself. Hence, when generalised, this indicates that for Lenin all minds must be both 'objective' and non-'objective' all at once, depending on from where they are viewed. And this seems further to imply that from certain viewpoints, the mind doesn't use any energy, while from others it does -- if from some directions it is material, but from others it isn't!

[Recall, Lenin has, as yet, no proof there are any 'other minds'; all he has are 'images' of what he takes to be human beings -- and hence 'images' of 'mind-possessors', to coin a phrase. Since they seem to be external to his mind, they must be material, if they exist and if his criterion is valid.]

It might be thought that the above difficulties could be circumvented if all minds were lumped together and classified as non-objective (or non-material), as a sort of job lot. But, in that case, as a group mind, the human mind plainly couldn't be external to itself -- if Lenin's 'criterion' is applied literally. This brave response would clearly mean that this 'collective mind' wouldn't be 'objective', but would be non-material, and psychologists, for example, should abandon their claim to study 'objective' features of reality embodied in the skulls of their subjects (now "clients"). If all human minds are 'non-objective', then it seems that study of them can't fail be tarred with the same 'subjectivist' brush. Psychology would thus cease to be an 'objective' science -- or, at the very least, its concerns and results could only ever be 'subjective'.30

Far worse, Lenin's thoughts about externalism, which surely once existed inside his mind, can't have been 'objective', either, by his own 'definition' (since they, too, couldn't exist outside themselves) -- and, by parity of reasoning, neither could any other DM-thought (about anything whatsoever) be 'objective'. In fact, given Lenin's 'definition', in the entire history of Dialectical Marxism, not a single one of its theorists has ever (or could ever have) had an 'objective' thought!

And if Lenin were right about this, he would be non-objectively right about it, too -- which blessed mental state might be of interest to his biographers, but would be of no concern to 'objective' science (or, indeed, to the rest of us) -- since the 'rightness' of his views would, of course, be 'subjective' by its own 'definition', in that he thought it at all. If we accept what Lenin had to say about 'objectivity' (that is, that for something to be 'objective', it had to be independent of the human mind), then nothing a DM-supporter had to say (even about 'objectivity' itself(!)) could be 'objective', could it?

"To be a materialist is to acknowledge objective truth, which is revealed to us by our sense-organs. To acknowledge objective truth, i.e., truth not dependent upon man and mankind, is, in one way or another, to recognise absolute truth." [Lenin (1972), p.148. Bold emphasis added.]

"Knowledge can be useful biologically, useful in human practice, useful for the preservation of life, for the preservation of the species, only when it reflects objective truth, truth which is independent of man." [Ibid., p.157. Bold emphasis added.]

Moreover, just as soon as such thoughts entered the world (as materially spoken or written tokens in the air, in books, or in newspapers (etc.)), they would plainly become "external" to the mind, and would therefore become 'objective' (given Lenin's 'definition').

Unfortunately, that means that while DM-thoughts can't be 'objective', DM-sentences (etc.) themselves, when spoken or written, can be and are 'objective' -- including the false ones. Indeed, false sentences are just as 'external to the mind' as those that are true. Furthermore, and by the same token, the negation of any and all DM-theses (when written down or spoken) must be 'objective', too!30a0

On the other hand, such sentences aren't independent of the human mind. If so, and if Lenin is to be believed, they can't be 'objective'/material, they must be 'subjective', after all! But, if we take Lenin's "independent of man" caveat too seriously, nothing in human history or society would be objective, and that includes revolutions! Furthermore, that would mean that it would be impossible to appeal to practice in order to ground any of this in objectivity, since practice isn't "independent of man", either. Out of the window goes that core DM-concept!

This in turn means that just as soon as anyone reads or hears these formerly and supposedly 'objective' DM-sentences (etc.), they would become non-objective again, since they would now be part of the content of someone's mind (and hence no longer "external" to all such). But, that would mean that no one could read, interpret or regard a single DM-thesis as 'objective' unless they succeeded in keeping it 'out of their minds'. [This might be one contradiction that not even ultra-orthodox dialecticians will want simply to "grasp".] Hence, if anyone were to conclude that such an 'external' sentence was 'objective', they could only do so by means of a 'non-objective' thought to that effect -- or, indeed, by not thinking it! In that case, they could conclude nothing about the meaning of any physical embodiment of a DM-sentence without compromising its 'objectivity' -- that is, as Lenin conceived things.

At this point, it would surely tax the patience of any reader who has made it this far if the above 'objective' sentences -- in that what they say is 'objective' just in case they are aren't read or understood by anyone, if Lenin is to be believed -- were dwelt upon any longer. However, odd though this might seem, the content of the above words will be 'objective' only for those who haven't made it this far, who have never read them, or who didn't understand them -- again, if Lenin is correct. And the same goes for anything written in MEC and other DM-books or articles; their content is 'objective' only if no one, including the original author, ever read them!

It is perhaps unnecessary to underline the confusion that would be introduced into epistemology if Lenin's non-objective thoughts about 'objectivity' were ever taken seriously. Fortunately, only those already "suffering from dialectics" (to quote Max Eastman) seem foolish enough to do so.

However, Lenin's 'criterion' faces far more serious problems than the relatively minor 'difficulties' that have already been aired.

Despite the damaging conclusions that follow from some of the things Lenin unwisely committed to paper (examined earlier), he had other things to say about our knowledge of reality (incidentally, which was part of one of the few detectable arguments in the entire book!) that raise serious difficulties of their own:

"Our sensation, our consciousness is only an image of the external world, and it is obvious that an image cannot exist without the thing imaged, and that the latter exists independently of that which images it. Materialism deliberately makes the 'naïve' belief of mankind the foundation of its theory of knowledge." [Ibid., p.69. Bold emphasis added.]

This shorter passage is even clearer:

"The image inevitably and of necessity implies the objective reality of that which it 'images.'" [Ibid., p.279. Bold emphasis added.]

Both of these appear to commit Lenin to the idea that if it is possible to form an "image" of something it must of "necessity" exist, since "an image cannot exist without the thing imaged, and the latter must exist independently of that which imagines it", and an "image inevitably and of necessity implies the objective reality of that which it 'images'". So, not only must it exist, it must exist "objectively".

Unfortunately, once more, Lenin forgot to say how he knew this was the case. It looks like he, too, was imposing yet another dogmatic idea on reality.

In Lenin's defence, it could be argued that this fact (if fact it be) is tautological: "an image cannot exist without the thing imaged" -- if by this he meant that "the thing imagined" exists in the mind of the one doing the imagining/imaging. In that case, Lenin would be pointing out the obvious but uninspiring fact that if an image exists (in the mind of the one doing the imaging) then manifestly it exists in that mind.

That interpretation would undermine seriously Lenin's 'materialism', which as we have seen, depends on our images reflecting objective reality. If they merely reflected what was in the mind, and only that, he would be no different from a solipsist.

Of course, the above proffered attempt to defend Lenin was shot down in flames by Lenin himself:

"The image inevitably and of necessity implies the objective reality of that which it 'images.'" [Ibid., p.279. Bold emphasis added.]

"[T]he sole 'property' of matter with whose recognition philosophical materialism is bound up is the property of being an objective reality, of existing outside our mind." [Lenin (1972), p.311. Bold emphasis added.]

So, if 'the mind' "images", say, an apple, it must exist objectively -- i.e., it must exist outside and independently of the mind. The problem is that this is in effect an blank epistemological cheque that Lenin has just signed, since it implies that if we can form an image of something it must exist, no matter how fanciful that image is. I will return to explore that unexpected consequence below.

Even if this were (implausibly!) what Lenin meant, the rest of what he says can't be right. It certainly isn't tautological that whatever is imagined "exists independently of that which imagines it", that is, that such things exist in 'objective reality'. It may or may not be true that imagined things actually exist 'outside the mind', but it certainly isn't the obvious truth that Lenin seems to think it is (that is, if we go along with this traditional way of depicting things for the moment)'; and it certainly doesn't follow that images imply the independent existence of the objects we take them to reflect (that is, if we do).

It could be argued that the word "image" implies that an image is an image of something, which is all that Lenin needs. Whether or not the word "image" does in fact imply this we will leave to one side for now, but one thing it does doesn't imply is the independent, 'objective' existence of whatever that image is an image of. If that were so, scientists could abandon research and engage in day-dreaming. Plainly, just because Lenin imagined that what he said was true, that doesn't make it true.

In fact, Lenin's claim is far from true; as will be demonstrated presently (here); there are many things which actually exist that we can imagine not to exist -- indeed, we can even form images of things being destroyed, or having been destroyed. And, it is also true that there are many things that we can imagine (or form images of) that do not and have never existed, as well as those that couldn't exist.

As is well known, one of Lenin's conclusions in MEC was that scientific knowledge is based on a reflection of the 'objective' world in the minds of observers or inter-actors, suitably revised over time. However, as is equally well known, representative theories of perception and knowledge (like Lenin's) have (i) Motivated the dogma that what we might take to be 'objective' features of the world are no more than 'subjective', inner shadows of dubious provenance, or they have (ii) Prompted the idea that 'reality' itself is just the play of "impressions", "sensations", or "qualia" in 'the mind'. Indeed, it could be argued that Lenin's "externalism" actually invites Idealist conclusions such as these, even though he declared himself an implacable enemy of any and all theories that overtly or covertly imply anything like it.

In the present case (concerning "images in the mind"), this worry isn't helped by the awkward realisation that despite Lenin's confidence in the deliverances of scientific theory, practically every theory that has ever been constructed has been wrong -- in many cases wildly wrong. [This claim will be substantiated in Essay Thirteen Part Two; in the meantime, see here.] In fact, with respect to Traditional Philosophy, considerations like these have always stood in the way of the formation of convincing epistemological theory of knowledge -- at least one that hasn't been supported by a sufficiently robust ontology.

In view of the fact that MEC has been -- and still is -- widely regarded by revolutionaries as the definitive response to Phenomenalism (etc.) -- if, that is, it is beefed up with material taken from PN --, naïve readers would be forgiven for thinking that MEC aired a series of devastating counter-arguments, which severally or collectively, but decisively, consigned every other rival theory to the philosophical dustbin of history.

However, as it turns out, MEC is largely an argument-free zone. Having picked through the endless pages of bombast, repetition and bluster that fill most of this book, I have been able to locate and identify only a handful of clearly recognisable philosophical arguments that Lenin marshalled in order to substantiate his hyper-bold claims, and which present a superficially credible challenge to Phenomenalism, etc. In place of a considered, critical response to alternative theories, Lenin almost invariably resorted to invective, ridicule, sarcasm, invention and abuse. Elsewhere, in order to settle issues where even his own wafer-thin arguments could be stretched no further, Lenin clearly thought it enough to quote the DM-classicists (most notably, Engels) as authorities. Failing that he limited himself merely to asking a set of rhetorical questions -- many of which would have been more profitably directed at his own theory --, all the while constantly repeating the "externalist" mantra as if it were some sort of talisman. It isn't without justification that MEC has been described as "Philosophy practised with a mallet".

Now, for those already convinced on other grounds that MEC is the non-existent deity's gift to polemic, this is all good, knock-about fun. However, for those not so easily amused (or bemused), a more pressing question suggests itself: Why have generations revolutionaries been so easily taken in by hundreds of pages of repetitious, ill-informed, abusive and ignorant bluster?

By any standards, MEC is easily one of the worst books ever to have been written on Philosophy --, certainly by a revolutionary.

And I say that as a dyed-in-the-wool Leninist.

Fortunately, there is far more to the refutation of the (epistemological) content of MEC than a handful of impertinent accusations and allegations, like those above.

As noted earlier, one of the few recognisably philosophical arguments to be found anywhere in that book (aimed at countering the theories promoted by Idealists and Phenomenalists, etc.) is the following:

"Our sensation, our consciousness is only an image of the external world, and it is obvious that an image cannot exist without the thing imaged, and that the latter exists independently of that which images it. Materialism deliberately makes the 'naïve' belief of mankind the foundation of its theory of knowledge." [Lenin (1972), p.69. Bold emphasis added.]

"The image inevitably and of necessity implies the objective reality of that which it 'images.'" [Ibid., p.279. Bold emphasis added.]

That's it! On the basis of this half-formed, quasi-argument, Lenin hoped to counter philosophical theories some still regard as definitive -- especially when they are set against the sophomoric version of naïve realism Lenin tried to advance in MEC.

[I hasten to add that I don't consider the aforementioned philosophical theories in any way definitive! In fact, I regard all philosophical theories as incoherent non-sense. Again, I am merely drawing attention to Lenin's self-defeating approach to such questions in MEC.]

Before we consider whether or not Lenin's argument is successful in its own right, it is worth pointing out (to those dialecticians who question the deliverances of 'commonsense' -- which I take to be more-or-less the same as "naïve realism" referred to by Lenin --, and who also regale us with the 'appearance'/'reality' distinction) that 'commonsense' can't in fact be called into question if it is to act as a basis for Lenin's theory of knowledge.

[Those who think this is an unfair criticism of Lenin should read on before they draw that rather hasty conclusion.]

Despite this, and given the other complexities that DM introduces, Lenin's alleged foundation stone soon starts to crumble into dust. According to DM-epistemology, knowledge depends on the completion of an infinite process before the very first thing can be known about anything in the DM-"Totality" with anything other than infinite uncertainty.

As we have seen (follow the previous link for proof), this approach to knowledge means that nobody is in any position to determine what even a simple tumbler is before everything about everything is already known.

In reply, it could be argued that the above anti-DM counter-claim is just another unfair caricature of dialectical epistemology. But, it is worth remembering that anyone who objects on those lines is similarly in no position to assert it successfully until we are given a clear (and non-defective) account of DM-epistemology. After only 150+ years, we are still waiting.

Indeed, given DM-epistemology, no one would be in any position to assert that the above anti-DM counter-claim is unfair and know they were speaking the truth until they too had completed the aforementioned infinite ascent of 'Epistemological Mount Olympus'.

This means that all forms of 'dialectical knowledge' are permanently trapped in this sceptical quagmire -- that is, if Engels and Lenin are to be believed.

[The above seemingly controversial claims were fully substantiated in Essay Ten Part One. Readers are directed there for more details.]

Despite this, it is worth reflecting on the sort of response that, say, a Phenomenalist might make to Lenin's assertion that his theory begins with the "naïve" beliefs of ordinary folk, and builds from there:

"The 'naïve realism' of any healthy person who has not been an inmate of a lunatic asylum or a pupil of the idealist philosophers consists in the view that things, the environment, the world, exist independently of our sensation, of our consciousness, of our self and of man in general. The same experience (not in the Machian sense, but in the human sense of the term) that has produced in us the firm conviction that independently of us there exist other people, and not mere complexes of my sensations of high, short, yellow, hard, etc. -- this same experience produces in us the conviction that things, the world, the environment exist independently of us. Our sensation, our consciousness is only an image of the external world, and it is obvious that an image cannot exist without the thing imaged, and that the latter exists independently of that which images it. Materialism deliberately makes the 'naïve' belief of mankind the foundation of its theory of knowledge." [Ibid., pp.68-69. Bold emphases alone added. Quotation marks altered to conform with the conventions adopted at this site.]

She (the supposed Phenomenalist) might wonder what, for instance, the word "image" is doing in such prosaic surroundings. Indeed, she might even suggest that if we were to ask the average human being about their knowledge of the world, the word "image" would appear nowhere in the reply.

Hence, not only is the aforementioned dialectical meander through infinite epistemological space counter-productive (since it implies infinite and permanent ignorance of everything and anything), it begins in the wrong place! 'Commonsense' and/or "naïve realism" -- whatever they are -- neither start nor end with 'images'.

[Admittedly, certain forms of phenomenalist psychology might do so, but 'commonsense' doesn't. Or, if it does, we still await the proof. That 'proof' would be worthless, anyway, since it, too, would merely consist of, or would be based on, yet more 'images', if Lenin were to be believed!]

It is worth pressing this point home: there is no evidence that the "naïve" beliefs of anyone -- not even the naïve beliefs of Dialectical Marxists -- are based on 'internal images', but there is much to suggest they aren't. Hence, there is no evidence that ordinary people, or even sophisticated socialists, believe any of the following (that is, before they had encountered the DM-classics, traditional epistemology and/or 'pop science'):

"Our sensation, our consciousness is only an image of the external world…." [Ibid., p.69. Bold emphasis alone added.]

"The gist of his theoretical mistake in this case is substitution of eclecticism for the dialectical interplay of politics and economics (which we find in Marxism). His theoretical attitude is: 'on the one hand, and on the other', 'the one and the other'. That is eclecticism. Dialectics requires an all-round consideration of relationships in their concrete development but not a patchwork of bits and pieces. I have shown this to be so on the example of politics and economics....

"A tumbler is assuredly both a glass cylinder and a drinking vessel. But there are more than these two properties, qualities or facets to it; there are an infinite number of them, an infinite number of 'mediacies' and inter-relationships with the rest of the world.... Formal logic, which is as far as schools go (and should go, with suitable abridgements for the lower forms), deals with formal definitions, draws on what is most common, or glaring, and stops there. When two or more different definitions are taken and combined at random (a glass cylinder and a drinking vessel), the result is an eclectic definition which is indicative of different facets of the object, and nothing more. Dialectical logic demands that we should go further. Firstly, if we are to have a true knowledge of an object we must look at and examine all its facets, its connections and 'mediacies'. That is something we cannot ever hope to achieve completely, but the rule of comprehensiveness is a safeguard against mistakes and rigidity. Secondly, dialectical logic requires that an object should be taken in development, in change, in 'self-movement' (as Hegel sometimes puts it). This is not immediately obvious in respect of such an object as a tumbler, but it, too, is in flux, and this holds especially true for its purpose, use and connection with the surrounding world. Thirdly, a full 'definition' of an object must include the whole of human experience, both as a criterion of truth and a practical indicator of its connection with human wants. Fourthly, dialectical logic holds that 'truth is always concrete, never abstract', as the late Plekhanov liked to say after Hegel...." [Lenin (1921), pp.90-93. Bold emphases alone added; quotation marks altered to conform with the conventions adopted at this site. Several paragraphs merged.]

In order to see this, consider the following example; suppose worker, NN, asserted the following:

L1: "That policeman hit me over the head with a truncheon!"

Now, only a rather desperate cop-defender would respond with this remark:

L2: "You are mistaken. What you experienced was in fact only an image of a policeman assaulting you."